It's clear that there has been some arguing between the Eisteddfod Council and the local committee in Swansea following the previous Eisteddfod.

According to all the newspapers (and none of the papers explain the history in an easy to follow way), the Council expected the officials of the 1863 Eisteddfod to return £50 each from the profits made to the Council. The money was returned by one of the officers, but not by Gwilym Tawe. The argument continued for some time before exploding at the Council meeting at the Eisteddfod in Llandudno.

The Welsh press were complaining that the Eisteddfod had become too English, and that the Welsh were bowing down to the English audience, while the English press felt that the Eisteddfod took pride in belittling the English language and English visitors during the week.

Unfortunately, copies of some of the papers ar not available on the National Library’s website. It would have been interesting to read the Seren Cymru and the Baner ac Amserau Cymru reports looking back at the week as a whole. This would have allowed us to get a clearer picture of what happened, but we can only use the resources available at this time.

So, with all the bad feeling before the festival even began, it did not bode well for the week, although the Pavilion was praised across the board in both Welsh and English in the lead-up to the week. Of course, there had been big problems with the Pavilion in Swansea the previous year, with one of the beams cracking and starting to fall during one of the evening concerts. Therefore, the Llandudno committee wanted to emphasise that the Pavilion in 1864 was going to be better than any previous eisteddfod building.

This article in Seren Cymru on 19 August 1864 shows that the organisers, and the makers of the Pavilion had been hard at work and that the 19th centurey PR machine was in good working order!

“We understand that major preparations are going well in Llandudno opposite the National Eisteddfod held there next week. The pavilion is completely finished, and will be one of the most beautiful buildings ever built to host an Eisteddfod. It is octagonal in form, with a broad ascension at one end; and is therefore in the most advantageous form to see and hear. The land on which it is built rises steadily, which will be good for one to see over the other. It has a felt roof, and will therefore be completely waterproof and windproof. Its interior is also wonderful; when a man enters through the appropriate entrance with his ticket, he will be in the correct section of the building and will not have to push across other people to get to the right part of the pavilion.

There was a similar article in the The Aberystwith Observer on 27 August, “We find that the pavilion, which is one of the largest, best arranged and most imposing erections ever seen in Wales, was completed on Friday with the exception of the in-door ornamentations, which are chiefly carried out under the management of professional taste and talent of the architect, Mr Felton, and the business promptness of Mr. Prichard the builder. The general arrangements are perfect and leave nothing to be desired.

“We are glad, too, to find that proper care has been taken to secure ample ventilation, ans should more be required it can easily be obtained by simply removing one of the top boards around the building. The retiring room for the lady and gentleman artistes are most conveniently fixed under the orchestra, and are spacious, private and commodious… Altogether, the pavilion is a credit to Wales and to all parties concerned in its erection.”

And there was more praise for the Pavilion in the The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality on 27 August, “The decorations of all kinds was something immense as well as beautiful, and were solely the handiwork of the members of the Ladies’ Committee, presided over by Mrs. Morgan, of the Rectory, to whom too much praise cannot be awarded for their taste, patriotism and industry. The decorative department of the pavillion was under the superintendence of Mr. Morrell.

“In order to render the Eisteddfod more attractive and more in accordance with its new character, the Council exhibited, in front of the platform, several specimens of sculpture, the work of Mr. David Davies, a Welshman now residing in the metropolis. The same artist also sent a full life-size figure of Alexander, when roused to fury by Timotheus, he seized the flambeau to fire Presopolis. There was also exhibited a large case of excellent photographs of literary and musical celebrities, chiefly connected with Eisteddfodau.”

But the Welsh press was less positive about the arrangements for the Eisteddfod, and on 13 August, Y Gwladgarwr issued the following warning, suggesting that the Llandudno Eisteddfod would not be a success. “The Eisteddfod is to be held this year in the ancient town of Llandudno, North Wales, on the 23rd, 24th, 25th and 26th of the current month. This Eisteddfod does not create much excitement in South Wales, as it is also not about North Wales. The committee's operations are hidden from the public, and no-one knows anything about the list of competitions as they were not published in one of our principality's newspapers. We can ensure that the Llandudno Eisteddfod committee made a big mistake by not making the Eisteddfod competitions known through the newspapers; the committee can be sure that we will be counting the cash receipts the following day for the Eisteddfod.

“We condemn the current practice of using the National Eisteddfod to satisfy the favour of the English, at the expense of neglecting the Welsh language; and we know that this custom causes many patriotic Welshmen to abandon our eisteddfodau. Let it be our National Eisteddfod, in any case, to be Welsh; or remove the word 'National' from its association and replace with the word 'English'… We hope that the Aberystwyth committee will take note, and be careful not to emulate the previous committees in their Englishness. Remember, 'The Eisteddfod,' (the main committee) as it claims itself to be National, that all its operations are open to the criticism of the Press and the Welsh nation, and that they will be watching and commenting. ”

Extremely strong words, and in the issue published on 3 September, immediately after the Eisteddfod, Y Gwladgarwr referred to the warning they had voiced weeks earlier, declaring the Eisteddfod a failure.

“There has been much speculation about the fate of the Eisteddfod; but now, its troubles are known to the public, open to criticism from the Press and the Welsh public. We are sorry to have to say that the Llandudno Eisteddfod was the poorest of the four national festivals held so far; yet we were not disappointed, as we had previously expressed our view that this was to be the case. How could they succeed, while the committee had failed to publish the list of competitions in the principality's newspapers.

“The timing of the Eisteddfod was not published in as much as one of the Deheubarth papers; and we saw nothing advertising its contents anywhere beyond the lands of North Wales.”

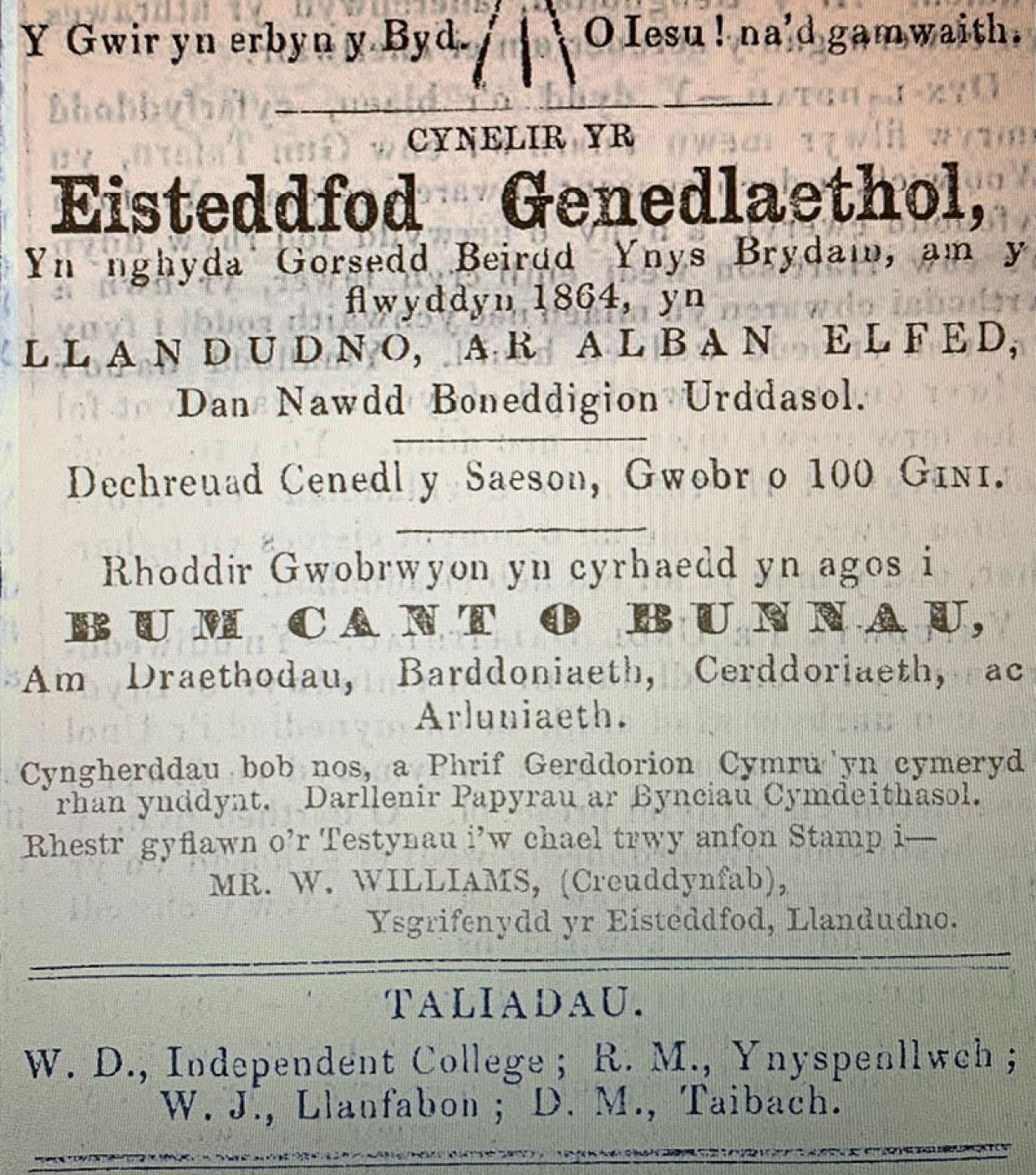

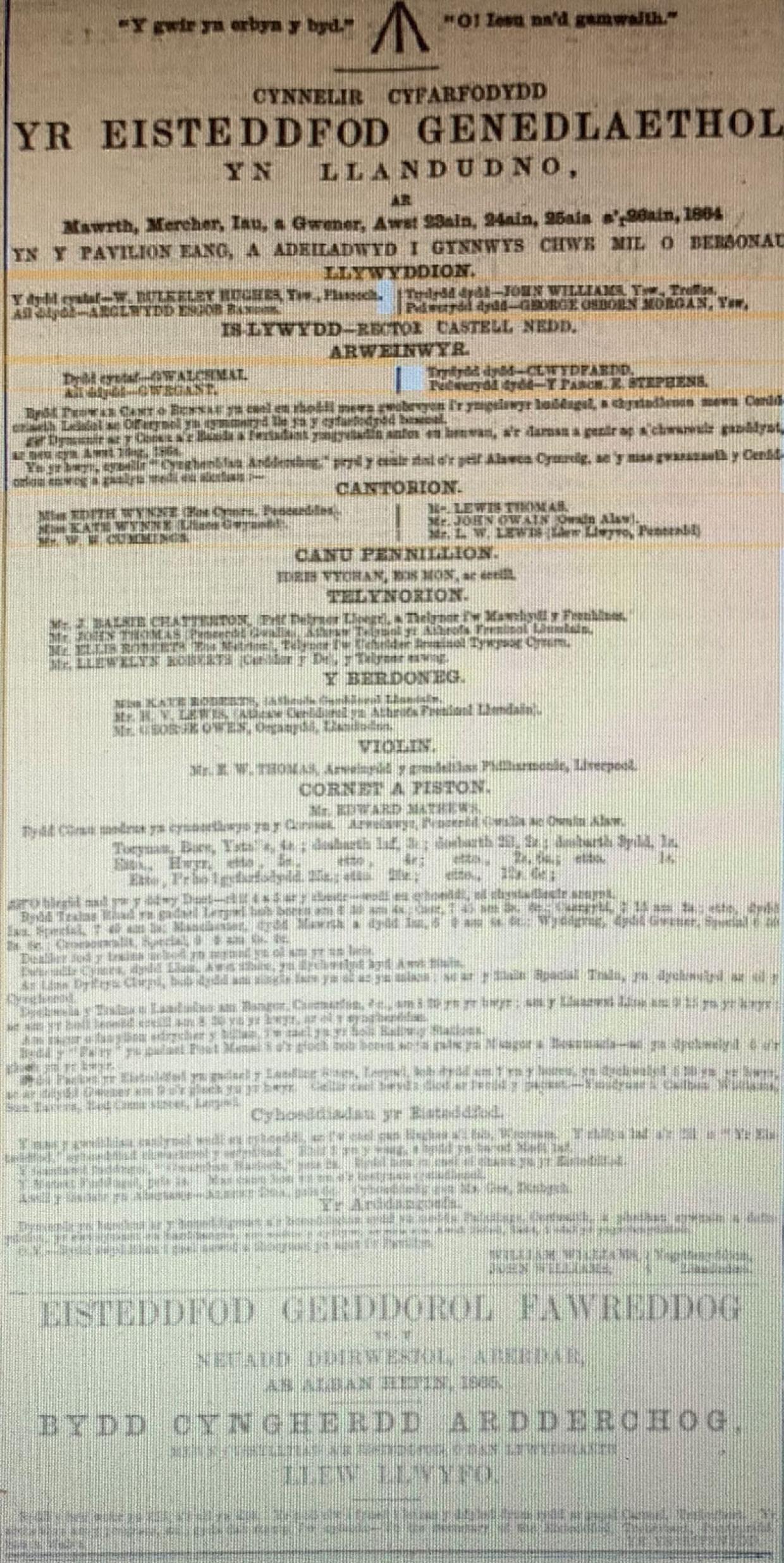

But the organisers did their best to attract visitors. Advertisements had appeared in the newspapers. The organisers had also made arrangements for people to visit the Eisteddfod from all over the north and beyond, but these arrangements may not have been widely advertised. Two weeks before the festival began, this report appeared in Seren Cymru on 19 August, “With regard to the conveniences of coming to town, they are all that you could wish for. A steamer leaves Menai Bridge every morning at eight o'clock, calling at Bangor and Beaumaris, returning from Llandudno at six in the evening. A steamer will also start from Liverpool every morning at seven and return around half past five. There will also be cheap carriages running from all neighborhood stations; and on the morning of Monday the 22nd, free carriages start from the South, and can visitors can return on any day during the week.”

This all seemed very well organised, but clearly, it wasn't just enough to draw large crowds over to Llandudno at the end of August, nor was it enough to garner the support of the Welsh press. Was there a future for the National Eisteddfod following such an awful year, or would the new organisation cease to exist after just four years? We’ll have to look forward a year to 1865 to see what happened next in the history of the festival.